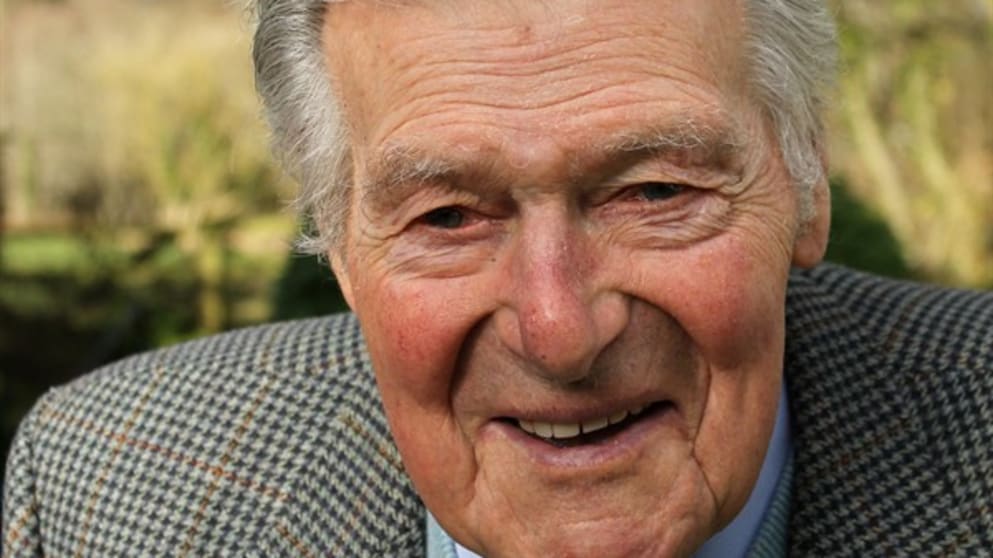

To mark the 40th anniversary of the first European Tour event, europeantour.com sat down with its founding father, John Jacobs OBE. In this, the third and final instalment in a series of features, we look at John Jacobs – the teacher, and explore the methods that have been embraced by the very best in the business.

The principle of causality, in its most rudimentary form, is essentially a simple one.

The theory explores the relationship between two events and considers that one has occurred as a direct consequence of the other, a philosophy that John Jacobs has long made the cornerstone of his teaching mantra.

Jacobs, though, as is so often the case, has a way of putting things to make them appear altogether more straightforward, a characteristic planted at the root of his extraordinarily successful coaching career.

“Cause and effect,” he opens definitively, in such a way as to emphasise each word as if it were an individual utterance. “It was always about teaching people; it was always about the flight of the ball; it was always about realising that the only function of the golf swing is to deliver the club head.”

Simplicity has always been paramount in the fundamentals of Jacobs’ teaching methodology, a centred approach based around one key factor – how the ball reacts after it has left the clubface – and it was an idea that not only changed the face of golf tutorship when he introduced it in the 1960s, but one which has also inspired coaches to this very day.

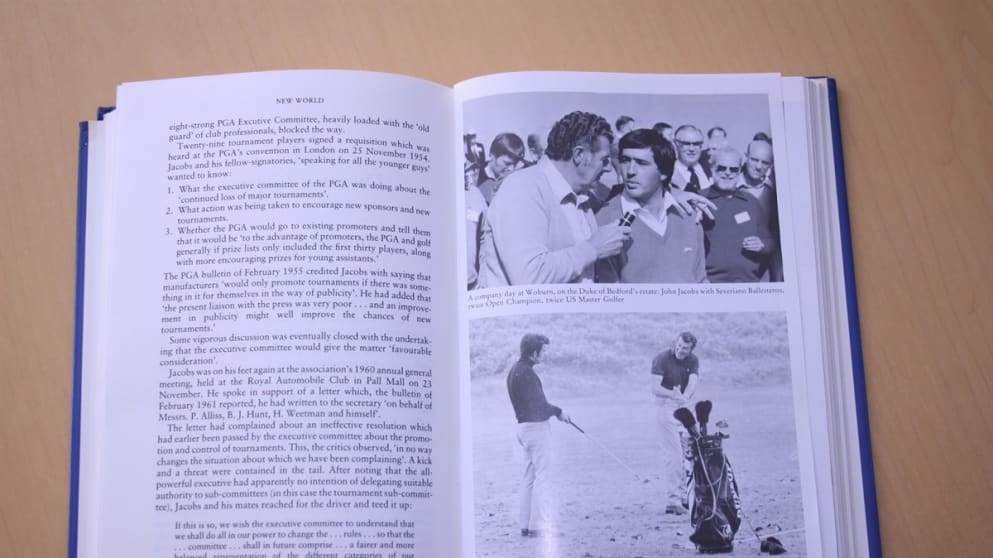

Most importantly of all, however, his breakaway methods grabbed the attention of golf’s leading lights, and at one time or another he has taught, or at least advised, no lesser names than, Seve Ballesteros, Tony Jacklin, Jack Nicklaus, Greg Norman, José María Olazábal, Tom Watson and so many more.

Teaching is an inherently results-driven business and Jacobs’ simple theories frequently produced rapid improvements through the smallest of alterations, a corollary that has endeared him to the very best purveyors of the sport.

In the introduction to his magnum opus written with Ken Bowden – former editor of Golf Digest – and first published in 1972, Practical Golf, Jacobs penned what had already become his steadfast credo when it came to teaching golf. Some 40 years on, on a chilly late winter’s morning, he spells out the same doctrine almost word for word, so ingrained it is into his psyche he doesn’t even pause for thought.

Jacobs’ revolution was that he would diagnose a pupil’s golf swing from the flight of their ball, analysing the effect then working backwards to establish the cause before determining the necessary correction. It was brilliantly simple and it proved highly popular.

“It sounds silly,” he prefaces, “but technically, golf is a much simpler game than most people realise. It’s almost self-explanatory. Mishits are so often simply caused by one of two things: an open clubface or a closed one. We called it the “geometry of impact”, and it is just logical.”

Jacobs has always placed his students at the core of his coaching approach, a pivot round which to implement his unique style, “I don’t teach a method, I teach people,” he says determinedly, and he identifies his own struggles as a schoolboy at Maltby Grammar School as a key influence in his success as a coach.

“I was never any good at school but I’ve always been logical,” he says. “I was a slow learner, but I also felt that my teachers’ explanations were rushed and lacked explanation. Once it had been repeated to me, slowly, it was no longer confusing and would then stick. It taught me the principles of how I would go on to teach golf.”

Jacobs is a people person; he is as engaging and entertaining as he is informative, and upon meeting him you sense immediately the characteristics that made him just so popular as a teacher. His talents of demonstration were no less impressive than that of a concert pianist who can improvise a soaring cadenza midway through a Beethoven concerto; he could shape the ball this way and that, left-right-high-low, push-pull-slice-hook, mimicking a student’s flaw with his own swing to reproduce the same results and sometimes even identifying a fault with his back to a pupil’s swing, merely from observing the ball’s path through the air. “That wasn’t me showing off,” he stresses, “that was letting them all know that I know.”

Even before he had fully established his revolutionary approach to coaching, Jacobs’ affable disposition had endeared him to his punters from his earliest forays into teaching at Hallamshire – where he was assistant professional after leaving the RAF in 1947 – and subsequently at Gezira Sporting Club in Cairo – where he moved in 1949 with his wife Rita – and his lesson books were always brim full with bookings.

After returning from Egypt to begin what would prove a modestly successful career as a tournament professional, Jacobs took on the role of professional at Sandy Lodge, just outside of London. His teaching proved no less popular there and he found himself, although he is at pains to admit it, resenting the distraction somewhat.

“I hated teaching at Sandy Lodge,” he confesses. “Don’t get me wrong, they were wonderful people, I was very happy there and it was satisfying to know I was wanted and helped people, but it was at a time when I wanted so much to be working on my own game.”

Jacobs tried, to no avail, to stem the flow of customers by hiking up his lesson fees but it had no effect, his lesson book remained booked up for weeks to come.

Having never quite achieved the levels of success as a player that he had so vehemently desired – “I was always mad to be a great player,” he says – Jacobs was somewhat a victim of his own success as a coach (even turning down two invitations to play the Masters Tournament thanks to a bulging lesson book in the mid-‘50s) and he hung up his bag and retired from life as a tournament professional at the age of 38 in 1963.

The tournament scene’s loss, however, was to be golf’s gain.

Peter Dobereiner, in the preface to Laddie Lucas’ biography on Jacobs, issues a call of thanks to the decision: “John Jacobs once told me that it was not until he retired from competitive golf that he began really to understand the swing, adding wryly ‘If only I had known then what I know now’. I am glad that he ordered his career in this back-to-front manner. The world may have lost a great player but they are ten a penny. But because John turned his intelligence and energies to teaching whilst in his prime he was able to develop into one of the most significant figures in contemporary golf as a coach.”

It was in this period that Jacobs established his Practical Golf Schools, institutions advocating his ground-breaking theory, and ones that continue to flourish today.

In 1962 Jacobs had made an important sortie into print in Golf World magazine at the behest of Ken Bowden – journalist, author and editor – to write instructional pieces, and the two formed an alliance that would have significant implications in Jacobs’ future.

He reflects: “Ken could put me down on paper better than I could, better than anyone could. And he of course later [in 1969] became the editor of Golf Digest in America – after they had realised what a genius he was – which really gave me an entrée to make my name over there.”

Bowden gave Jacobs the opportunity to espouse the virtues of his breakthrough teaching technique to the Golf Digest teaching panel, a formidable group that included Cary Middlecoff, Sam Snead and Bob Toski amongst others, and initially he faced no small resistance to his foreign concept.

“They were all wrapped up in Nelson, in Hogan, the square-to-square method, and Nicklaus, far too upright swings,” Jacobs remembers, “but they were all charming and we rarely fell out.”

Not only did they not fall out, but Jacobs won them over – and fairly quickly, as Bowden recalls: “From the pure logic of his argument they accepted he was right. He changed the thinking of the Golf Digest panel and, thereby, he changed the mass of American thinking about the golf swing.”

Nowadays, the point of impact is where all great teachers start, but at the start of the 1970s Jacobs was the trailblazer who put the theory into words and into a structured practice. “I was the first in that respect,” he says, “thank God people look at things that way now. I didn’t know I was the first, it wasn’t a conscious decision, I just knew that my focus was the ball.”

Over the years, Jacobs has been involved in many instructional books, but none more famous or renowned than his 1972 publication, Practical Golf. It was in 1971 that Jacobs and Bowden collaborated to put the tour de force together, putting into one piece of work the best of Jacobs’ teachings. Having been translated into a plethora of languages, release and re-released over the ensuing years, it remains one of the most successful instructional golf books ever produced.

Having admitted to at first hating teaching, Jacobs found a forum that far better suited his approach, revelling in teaching people to teach.

He says: “Immediately when I got into the group teaching business and I could go down a line of pupils: diagnosis; explanation; correction. I love that sort of teaching. It sounds awfully conceited, but I was bloody good at it and I wouldn’t move until they’d hit a really good shot.

“You can’t teach people how to teach without pupils and so they would all trail behind me and those people have all themselves now become very good teachers in their own right. I have some books by some of them and they are all very generous in saying where they got their style from.”

Two of those “very good teachers” happen to include Hank Haney and Butch Harmon – both now coaches to some of the world’s top players and globally known as men in the upper echelons of the coaching game.

“In Hank’s first book he was very kind,” Jacobs reflects. “He said: ‘John Jacobs is not the best golf teacher in the world; he’s the best golf teacher has ever been.” Meanwhile, Harmon was equally as effusive in his praise of Jacobs, once saying: “John Jacobs wrote the book on coaching. There is not a teacher out here who does not owe him something.”

Two of the great stalwarts of American golf, including the man widely regarded as the finest player to ever grace the earth, have in the past turned to Jacobs for advice.

Jack Nicklaus, when struggling from the tee in a practice round shortly before the 1969 Open Championship at Royal Lytham& St Annes turned to Jacobs – who was walking with the group – and said in exasperation: “Come on, you’re supposed to know something about it, what do you think?”

“Thank God for that,” Jacobs had replied. “I thought you'd never ask.” He told Nicklaus he needed to stand up straighter to allow a fuller turn inside, a correction he would make in later years to great effect.

And shortly before The 1981 Ryder Cup at Walton Heath, the second time Jacobs Captained the European Team, Tom Watson asked for some advice to which Jacobs responded: “With the match only a few days away? Not on your life.” Two years later at Gleneagles, Watson collared Jacobs and asked him, “What was it you were good enough not to tell me then?”

Jacobs remembers vividly: “I took a look at him and he got everything right except he was using his five iron with the flight of a four iron.” Not often one to toot his own horn, Jacobs also adds: “I like to think that’s why he’s still playing like he is, from some of the tips I gave him that day.”

Tony Jacklin, two-time Major Champion and four-times Ryder Cup Captain, once spelt this out: “I just wanted John for five minutes. I didn’t want him for thirty. He saw it all with me so quickly: attack on the ball, and what it was giving. Then alignment, set-up, shoulders, ball position, tempo. It was all there in five minutes.”

At times, though, Jacobs had to dig into his inner reserves of northern grit, a personality trait which helped him manage some of the game’s most colourful characters.

“I think I was a good teacher because I was sure of my ground and quite full of authority,” he speculates. “It wasn’t ‘I think you should’ it was ‘You should’.

“Seve was difficult to teach,” he continues. “I remember I was being very firm with him one day, and he said, ‘John, I am very strong when I’m playing’ and I responded, ‘Seve, I am very strong when I’m teaching.’ It just came out; I wasn’t trying to be clever or anything.

“At The Ryder Cup once when he was struggling he must have hit 300 drives for me in front of 2,000 people and probably all but four hit the fairway.

“All I told him was: ‘Don’t worry about your backswing, come from there and shift there; I’ve opened the door will you please shut it. Hit from the inside, clear the left side.’ That’s all he needed. The next morning Seve came back to me and said: ‘John, thank you for yesterday, I think I’ll stay as I am.’”

Jacobs maintains a special bond with one of Ballesteros’ closest allies in his lifetime, 2012 Ryder Cup Captain, José María Olazábal, who, knowing we were visiting his home, asked us to send Jacobs his warm wishes. The two are kindred spirits, lifelong outdoorsmen who love to fish and hunt, and Jacobs refers to him often throughout our interview by the affectionate cognomen ‘Chema’.

Olazábal wrote a touching tribute in Peter Dobereiner’s Golf in a Nutshell with John Jacobs that read: “John Jacobs is an extraordinary teacher, whose help and advice I have had the benefit of since boyhood. He is both patient and constant, and his influence on my golf and on Spanish golf has been enormous.”

Jacobs spent some time altering Olazábal’s grip with the driver and smiles when he says: “We are great buddies, but on the other hand he was very difficult to teach. Like Seve he is very strong minded. Oh yes, he didn’t accept anything unless I could prove it.”

The prolific and varied life that Jacobs has lived has been touched so often, by so many legendary names, that with barely any prompting the captivating tales and opinions simply pour unhindered from him.

For such an aficionado to the fate of the golf ball upon leaving the turf, I enquire, who does Jacobs consider the best hitter he ever saw?

“I was lucky enough to play three rounds of golf with Byron Nelson in 1955, after he’d retired, in an event at Thunderbird in Palm Springs and he just hit everything dead straight. The way he flattened his swing at the bottom with his legs was genius, unteachable genius. He remodelled his swing early in his career and said he knew after that he would never play badly again. What a wonderful thing to be able to say.”

And what does Jacobs believe is the most important quality of a truly great player?

Jacobs responds: “The thing that perhaps defines the best golfers that have ever lived is refinement of the golfing mind; the ability to play a hole with a completely clear brain after having a bad one before it.

“I used to say temperament one, technique two, physical three and Peter Thomson I would say had the most natural temperament of anyone in my era. I know him very well; I had played that exhibition match with him in Cairo in 1951 and he had been sitting in an old Constellation for six hours and was stiff as a board.

“He played the first nine holes hitting everything out of the heel but continued to get it up and down. He loosened up a bit and came home in 32 or something for a 68 and he had been struggling all day, but still did it, still got it done. That’s what counts.”

Having watched the greats of golf throughout this life, such as the aforementioned five-times Open Champion Thomson, what does Jacobs think when he looks at where golf, and golfers, have taken the sport in more recent times?

“The thing is, they are all so very good now,” he says. “I’m hugely impressed by the control of distance they have with their shots to the flag, the consistency and handling of their ball flights. All of the guys at the top, they just hit the ball so well, so pure. Their techniques these days are just so sound and I think that is thanks to the standard of teaching we now have.”

When Jacobs converses, his default setting is teaching. He clearly loves discussing the vagaries of golf technique, from swing paths and club arcs to grips and wrists, to legs versus arms, turns, and, predominantly, corrections. It is visibly as much of a fascination now as it ever has been in his seven decades of teaching.

Ken Bowden, in the foreword to the masterpiece that is Practical Golf, admirably sums up Jacobs’ God-given talent in imparting golfing wisdom: “Whatever he might have done in life he would have been good at himself, but probably even better at showing other people how to do it. He has the experience, the temperament, the authority, the knack, the vocabulary, and – although after an exhausting day on a driving range or practice ground he will deny it – the desire to teach.”

And so, yes, cause and effect; effect and cause.

American poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson, somewhat of an authority on such matters, famously once said, “Life is a perpetual instruction in cause and effect,” and never has there been more of a case in point than that of Jacobs’ own journey; it is a statement, an epitaph that was not only inscribed indelibly into the intricacies of his own golfing theology, but one that imbued his very life and career path.

Jacobs never intended to become the world’s finest golf teacher, “No, I was going to be the greatest player that ever lived,” he says, “but you can’t choose what gifts you are given.”

But thanks to his natural affinity in golf’s teaching sphere, by simply being so very good at it, the effect was that coaching overpowered all the other facets of his life in golf, be it his time spent as a player, administrator, television commentator, Ryder Cup Captain.

To put it another way: Jacobs has spent the majority of his rich life passing instruction on the game he loves. That he also achieved so much in all of the above fields, particularly in his establishment of The European Tour in the early 1970s, is all the more remarkable.

Despite losing some of his physical prowess in recent years thanks to the inevitable niggles of later life, Jacobs still has a net set up in his garden for those looking for drive-thru corrections to their technique. He also still likes to hit the odd ball in there himself.

“I have a stool set up next to the net,” he says, “so I can hit three balls, have a sit down, then hit some more. I might not strike them quite like I used to, but the game never leaves you.”

For a mind as brilliant as Jacobs, though, he often diagnoses a players fault by description alone.

Shortly before we arrived at his Lyndhurst home in Hampshire , England, he received a phone call from former Ryder Cup player and Vice Captain Paul McGinley who had been experiencing some recent difficulties with his game.

“I just asked him what his ball was doing with his five iron and knew exactly what was going wrong with the swing,” he says simply. “Diagnosis, explanation, correction.”

Perhaps it was the contact from McGinley, or the earlier message from Olazábal, but Jacobs – as lively and partisan a European golf fan as you are likely to find – has The Ryder Cup on the brain and it elicits a sparkle in those wise eyes.

With a look of steely resolve and compassion, an expression that reflects the famed temperament and golfing appetite that has spurred him on to such an eclectic career in the sport, Jacobs says emphatically: “I’m not one to try and muscle my way in, but I’d still back myself even now to provide a quick-fix to our Ryder Cup players in the heat of the match.”